In December 2017, the German Society for Rheumatology (DGRh) published their first guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of ANCA-associated forms of vasculitis (AAV) [1]. The AAV encompass granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly Wegener’s granulomatosis), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA, formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome), which all occur with autoantibodies against cytoplasmic antigens of granulocytes (ANCA). The most important target antigens in AAV are the enzymes proteinase 3 (PR3) in GPA and myeloperoxidase (MPO) in MPA and EGPA.

The guideline agrees to a large extent with that of the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR), the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR), together with the European Renal Association (ERA) and the Canadian Vasculitis Research Network (CanVasc) [2].

Diagnosis of ANCA-associated vasculitis

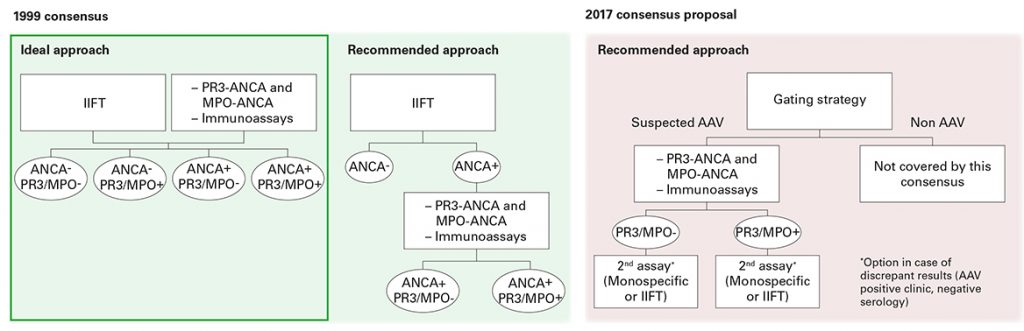

All four guidelines demand interdisciplinary care of the patients in centres specialising in vasculitis, since AAV can manifest in diverse clinical images [2]. Moreover, they all unanimously recommend performing ANCA detection by an indirect immunofluorescence test, combined with monospecific immunoassays for anti-PR3 and anti-MPO if there is a corresponding clinical suspicion [2].

At the international level, it is currently discussed to perform the two antigen-specific immunoassays as screening tests (Position Paper, [3]). This suggestion is mainly based on data from a retrospective multicentre study of the European Vasculitis Study Group with GPA and MPA patients. In the study, monospecific immunoassays (PR3, MPO) were compared with manual and automated ANCA immunofluorescence tests. As a result, today’s monospecific anti-PR3 and anti-MPO assays were attributed a diagnostic relevance at least equal to that of immunofluorescence tests [4, 5, 6]. The EUROIMMUN systems (IIFT: EUROPattern EUROPLUS Granulocyte Mosaic 25; ELISA: Anti-MPO ELISA, Anti-PR3-hn-hr ELISA) performed best in the comparison.

However, it must be mentioned that the study did not take into account consecutive samples of GPA and MPA patients, further vasculitis panels (EGPA) or other ANCA-associated diseases (e.g. ulcerative colitis or primary sclerosing cholangitis), for the diagnosis of which the new strategy is not suited. ANCA against non-AAV-associated target antigens such as DNA-bound lactoferrin, elastase, cathepsin G or BPI are not detected with the two monospecific immunoassays. Additionally, even experts point out in the new position paper that indirect immunofluorescence (11-17% negative) and immunoassays (9-16% negative) both detect ANCA in AAV patients who were negative using the respective other method [3]. Therefore, only the performance of both tests provides highest diagnostic certainty.

Possibly due to this and other aspects in the position paper which still require clarification, the new S1 guideline still follows the recommendations of the valid international consensus statements from 1999 and 2003 [7, 8], which argue for the combination of indirect immunofluorescence and monospecific immunoassays. In order to confirm a diagnosis, all expert groups recommend performing and analysing a biopsy [2].

Monitoring the disease course in ANCA-associated vasculitis

ANCA determination, however, has limited suitability for monitoring the disease course in a diagnosed AAV. Neither does a negative antibody finding exclude active disease, nor do increasing titers provide reliable prognosis of a possible relapse. Due to this reason, the guidelines of the DGRh as well as those of the EULAR/EAR and BSR stress that a modification of the therapy should not be initiated solely based on a change in titer or state of ANCA. It is recommended to regularly check the disease activity based on the clinical symptoms [2].

Up to now, there were no reliable activity markers for vasculitis available. A very promising candidate in vasculitis with kidney involvement is now sCD163 in urine [9]. CD163 is a membrane protein localised on the surface of monocytes and macrophages. The soluble form, sCD163, is produced by enzymatic splitting of the ectodomain as a response to proinflammatory stimuli. According to O’Reilly et al., activated macrophages infiltrate the glomeruli with beginning glomerulonephritis, a characteristic clinical manifestation of AAV, and secrete sCD163 into the urine. Corresponding to this hypothesis, the scientists found a close association of increased sCD163 levels in urine and active renal vasculitis. The sCD163 values in patients with acute vasculitis were significantly higher than in patients in remission stage, with other diseases, or in healthy control persons.

Therapy of ANCA-associated vasculitis

When deciding on a remission-inducing therapy, a distinction is made between AAV patients with and without potentially life- or organ-threatening manifestations. All four guidelines agree that if there is the possibility of organ damage, glucocorticoids should be administered together with cyclophosphamide or rituximab, while in AAV without possible organ damage a therapy of glucocorticoids and methotrexate is recommended. If remission is achieved, the treatment should be continued with a medium-strong immunosuppressive therapy (azathioprine or methotrexate) for 18 to 24 months [2].

Despite many similarities, there are also differences between the national recommendations [2]. According to Hellmich, this is due to a lack of data and particularities of the different national health systems. Nonetheless, the new guideline of the DGRh provides important assistance and orientation aid for clinicians who are treating AAV patients.

[1] Schirmer JH et al., Z Rheumatol https://doi.org/10.1007/s00393-017-0394-1 (2017) [2] Hellmich B, Z Rheumatol 76:133-142 (2017). [3] Bossuyt X et al., Nat Rev Rheumatol 13(11):683-692 (2017). [4] Csernok et al., Autoimmun Rev 15(7):736-741 (2016). [5] Damoiseaux J et al., Ann Rheum Dis 76(4):647-653 (2017). [6] Bossuyt X et al., Rheumatology (Oxford) 56(9):1633 (2017). [7] Savige J et al., Am J Clin Pathol 111(4):507-513 (1999). [8] Savige J et al., Am J Clin Pathol 120(3):312-318 (2003). [9] O’Reilly at al., J Am Soc Nephrol 27:2906–2916 (2016).